The gas in champagne and most other sparkling wines results from the addition of a small amount of sugar after fermentation has ended. After the sugar addition, bottle is capped. The sugar reacts with remnant yeast and converts to alcohol and carbon dioxide. Because the bottle is sealed, the CO2 gas enters the wine as a dissolved gas. The conversion of the sugar leaves residue particles in the wine that make it cloudy. When the sugar was added a small amount of clay was also added. The clay combines with the fermentation residue and help with precipitation (i.e. drag it out of solution). In a process called “riddling” the particles are encouraged to deposit in the bottle neck just under the cap. This deposit forms a plug that is then frozen and removed before the bottle is corked.

The gas in champagne and most other sparkling wines results from the addition of a small amount of sugar after fermentation has ended. After the sugar addition, bottle is capped. The sugar reacts with remnant yeast and converts to alcohol and carbon dioxide. Because the bottle is sealed, the CO2 gas enters the wine as a dissolved gas. The conversion of the sugar leaves residue particles in the wine that make it cloudy. When the sugar was added a small amount of clay was also added. The clay combines with the fermentation residue and help with precipitation (i.e. drag it out of solution). In a process called “riddling” the particles are encouraged to deposit in the bottle neck just under the cap. This deposit forms a plug that is then frozen and removed before the bottle is corked.

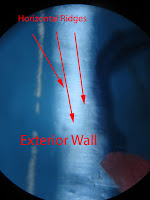

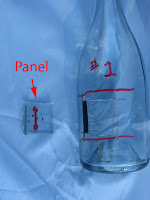

In this case the particles were attaching themselves to the interior bottle surface (photo upper left). The wine bottling experts at Read Consulting were asked to determine the cause of the problem. The problem was intermittent, and it had two potential causes. One hypothesis was that there were ridges on the interior wall that were “catching” the particles as they fell toward the cap. This hypothesis is not likely because the bottles are blow molded, and they should have a smoothe interior wall. Another possible cause was a new coating that was being sprayed on the bottle interior. There were horizontal ridges visible on the bottle; however, it was not possible to determine if these ridges were on the interior or exterior wall. The glass experts at Read Consulting cut a panel from the bottle and examined both surfaces microscopically. The ridges that were visible were on the exterior wall; thus, they were not responsible for the “sticking” particles. After the interior spray coating was eliminated, and the problem was resolved. The manufacturing defect is the interior spray caoting.